“What’s Land-grant?”

“What do you mean ‘What’s Land-grant’? You’re sitting in one.”

We were preparing to start our weekly lab meeting when the entire meeting was derailed by that innocent question. As usual, I looked around the table to allow someone else to answer, nothing. So I asked who in the room knew what a Land-Grant Institution was. Nothing. So I asked who knew what Morrill Hall on campus was named after? Nothing. I’m starting to hyperventilate. I’ve got the best students in the College in my lab. Sometimes I kid myself though. So the next week I asked a Junior level Honors College class. One hand was raised confidently out of thirty people, three to four others had heard of it.

I’ve discovered the root of our problems.

What’s Land-grant?

I’m not the first to realize this problem. Go no further than the title of the book “Reclaiming a Lost heritage: Land-Grant and Other Higher Education Initiatives for the Twenty-first Century” to realize it’s not a WSU-specific issue. As a friend told me, “that book should be required reading of every WSU employee.” The author, John R. Campbell, was the President of Oklahoma State University, a Land-Grant university from 1988-1993. In it, Campbell does a fine job of defining land-grant in historical and contemporary sense.

Historically, Land-Grant Universities were created by the Morrill Acts of 1862 and 1890 to form public universities of higher education in each state or territory from the proceeds of federal land sales. President Abraham Lincoln signed the law during the Civil War. To say that Lincoln saw education as the cure to the problems of the time is an understatement, “I can say that I view education as the most important subject which we as a people can be engaged in.” The original act states:

“An Act donating public lands to the several states and territories which may provide colleges for the benefit of agriculture and the mechanic arts… where the leading object shall be, without excluding other scientific and classical studies, and including military tactics, to teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts, in such manner as the legislatures of the states may respectively prescribe, in order to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes in the several pursuits and professions in life.”

Land-grants are a gift to the people, such that they may educate and save themselves. A map of Land-Grant and tribal universities is below:

The Land-grant mission has evolved through the years. Kenyon Butterfield, the former President of the University of Rode Island and driver of the Smith-Lever Act of 1914 that created the extension branches of land grant institutions, published many works on the problems afflicting rural communities of the 20th Century. Chapters in rural progress is one of several focusing on the problems of education for rural communities. Butterfield viewed the Land-Grant institutions as a great equalizer to bridge the socio-economic disparities already emerging between urban and rural life:

“We conclude, then, that the farm problem consists in maintaining upon our farms a class of people who have succeeded in procuring for themselves the highest possible class status, not only in the industrial, but in the political and the social order–a relative status, moreover, that is measured by the demands of American ideals. The farm problem thus connects itself with the whole question of democratic civilization.” Pg. 15

From this charge you could believe we have substantially succeeded in our Land-Grant mission. Whitman County, where WSU is located, is home to the highest percentage of millionaires (farmers) in Washington State. So is that it? Mission completed?

Contemporary Problems and the Land-Grant Mission

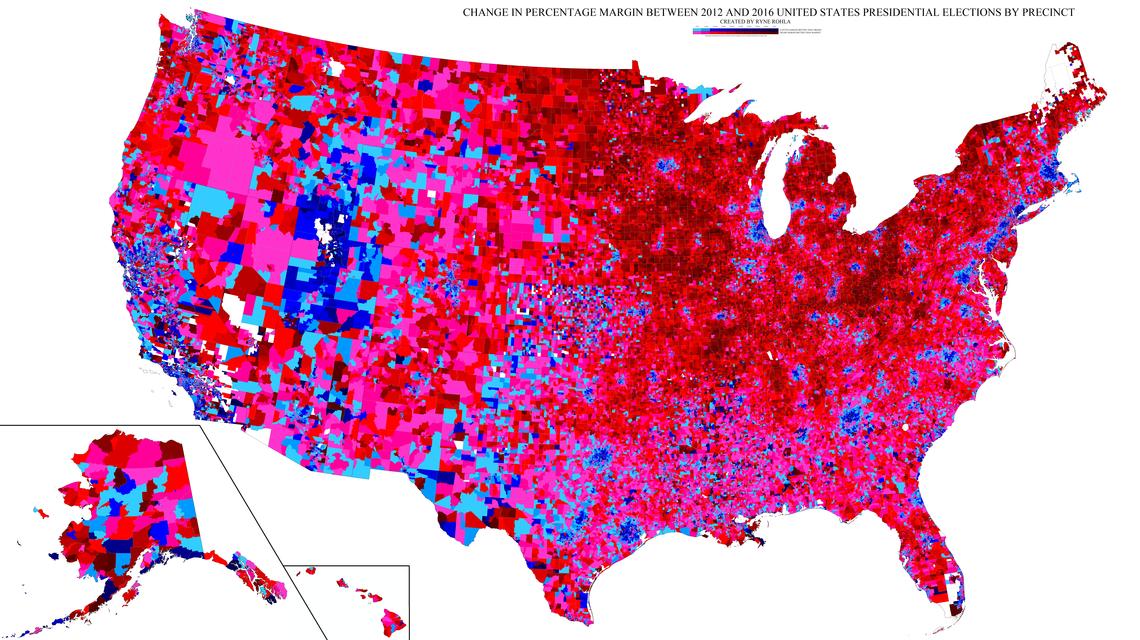

Many believe that the higher education system has aligned with a political party and is now being vilified by the other. The map below, developed by WSU graduate student Ryne Rohla, shows the change in voting tendencies across the US at the precinct level for the 2016 Presidential Election. What is clear to see is that the urban centers shifted harder to the left, the rural populaces generally harder to the right. This gaping rural versus urban divide is analogous to the divide that Kenyon Butterfield hoped the Land-Grant institutions would bridge.

Now, the 21st century challenge of the Land-Grant Institution has simply shifted from what Butterfield described. In many ways, the charge remains the same — Land-Grants serve as the grand equalizers between urban and rural life, it’s just that the divide may no longer be socio-economic disparities. In a world increasingly strained by the same energy, water, and food crises of old, we’re faced with the challenge of increasing the empathy and understanding of an ideologically divided populace that questions the very relevance of an education.

This problem, the question of the continued relevance of Land-Grant institutions, is of our own making. As Marcel LaFollete stated of research faculty in the book, “Stealing into Print: Fraud, Plagiarism, and Misconduct in Scientific Publishing“:

“To them, the word public is a dirty word. To them, their financial support just happens to come. Tax payers are never really seen as the source. If you look at the rhetoric, everyone talks about these issues as though funding just happened. It has been keeping them in a nice, middle-class life. The notion that the money came from people next door was a notion the community couldn’t grapple with. They were like politicians losing touch with their constituency. A sense of service just doesn’t fit into what they perceive is their reason for being.”

We’ve become obsessed with the metrics intended to describe our standing and placement among our peers. Not just as individuals, but as entire institutions. With this national and global focus and pursuit of the grand national funding whales, we’ve forgotten our identity in the roots of our rural and urban constituents. As evidence, when we as an institution looked inward to develop our Grand Challenges initiative in 2015, the first draft, as developed by WSU faculty, did not mention “Land-Grant” or refer to our charter mission once. After a steaming review from myself and others, the words were added into the final documents wherever possible. This shows that on many levels we, as an institution, have lost sight of our primary brand charter and mission. And as a result, we’re becoming a stepping stone for people seeking career advancement on the way to somewhere else. These traveling administrators hardly have the time to understand our own charter mission and brand promise, let alone the values of the people in our constituency.

Let me be clear, the problem is not the metrics. Metrics are important. The problem is focusing on the metrics, instead of the broader goals that implicitly drive the metrics. This metrics game focus, and competing to win, when our goal and mission is to bridge divides and connect, which everyone can win at, is a race to the bottom that won’t end well.

Re-discovering our Land and Mission

In 2019, WSU President Kirk Schulz, almost on a whim, decided to offer free copies to faculty of the new book “Land-Grant University For the Future: High Education for the Public Good” by Stephen M. Gavazzi and E. Gordon Gee (current president of West Virginia University and multiple other universities). Everyone of my colleagues I’ve asked are either reading it or have plans to read it. President Schulz has now scheduled a workshop to bring the authors to Pullman for community debate. The book offered a survey to all of the current presidents of Land-Grant institutions and tasked them with responding to the following positions:

- Concerns about funding declines versus the need to create efficiencies

- Research prowess versus teaching and service excellence

- Knowledge for knowledge’s sake versus a more applied focus

- The focus on rankings versus an emphasis on access and affordability

- Meeting the needs of rural communities versus the needs of a more urbanized America

- Global reach versus closer-to-home impact

- The benefits of higher education versus the devaluation of a college diploma

The authors frame this discussion within the goal of leadership via a service institution. Most will realize that these are forced dichotomies and that we really want all of the above. But the positions make you think strongly about what we are currently succeeding at, and how we could use our limited resources to position ourselves for sustaining success.

Now that I use this post to inform students of our Land-Grant mission, I hit the following point home: for WSU to remain relevant to our constituents takes engagement from the general public. We can’t help solve the problems of our region if our region doesn’t inform us of the problems they need solved. What will keep WSU relevant to you throughout your life? How will WSU remain a credible steward of our region’s future? How can WSU improve efficiency? Ultimately, how will WSU continue to fulfill what it means to be Land-Grant by bridging the urban-rural divide?

In the End

We live on a land of immense bounty and beauty called the Palouse. In a State of incredible social, biological, and geographical diversity in a prime phase of development. Washington likely has the best ratio of research faculty to supporting industry anywhere in the US. These roots can sustain. It is our continued mission. As Abraham Lincoln said, “You cannot escape the responsibility of tomorrow by evading it today.” For my fellow Faculty:

Put the paper or proposal down.

Name one of your constituents.

What county or town do they live in?

What are their biggest problems?

How are you working to solve these problems?

Now go one step further. Near your constituent there is a town with a school, a school full of children. For many, their dream in life is to solve those problems and they need you to help them realize this dream. Are you going to help them or take it away? Are you occupying the seat of someone that would help them? No? Ok, then what are you going to do about it?

Give this a shot: Get a group of them. Give the group a great challenge. Come up with ideas nobody has tried yet. Put the group in front of regional alumni, community leaders, and politicians — they’ll find the money, it’s their job. Now, accept the responsibility and commit to deliver. You’ve got just 4 years before your group will graduate.

Finished? Did it work? Great. Write that paper. Write a proposal to spread the concept nationally through other Land-grants. Pretty soon you’ve hit it big — just don’t forget your roots. Send your group back to their school. Have them tell stories about their accomplishments, and where they’re going next. You’ve won. Now repeat.

If enough of us do this, may’be we’ll all win. And may’be, somewhere along the way, we’ll stop taking this land, or its people, or our mission for granted.

If we choose not to, and the public continues to disengage from it’s Land-Grant universities, we’ll face the classic challenge of use it or loose it.