The student walked down the hallway led by a scientist in a lab coat. A room was opened and they were sat in front of a microphone and a button. “The instructions are simple” said the study administrator. “You are to teach a person in another room simple facts to remember. If they get one wrong, you are to press this button. Each time you press the button the amount of electricity they are shocked with increases; eventually you can reach up to 450 volts.” Then the study administrator left and the student was left in the role of the teacher, to shock the person in the other room if they got anything wrong.

The experiment started. The shocks coming after mistakes with increasing intensity. Screams could be heard in the other room accompanied by pleas due to heart conditions or other issues. Eventually the horrifying screams, after an agonizing duration, abruptly stopped and the study was over.

What the student didn’t know was that it was all a setup. There was no person in the other room and nobody was being hurt when the button was pressed. There was an actor staging the screams. And, perhaps even more tragically, to preserve the credibility of the study, participants sometimes did not find this out until months after the test. Some were permanently traumatized.

This famous experiment conducted at Yale in 1961 by Stanley MIlgram had a horrifying result: a shocking 65% of the hundreds of participants kept pressing the shock button all the way to 450 volts. More than enough to kill a person. It’s how the adverb ‘shocking’ originated. The results, showing a blind human “obedience” to following orders, have been used to explain atrocities from the Holocaust to Abu Ghraib. As cited in the Atlantic article, Arthur Miller, co-editor of the Journal Social Issues said this of Milgram’s experimental participants, “They’re not psychopaths, and they’re not hostile, and they’re not aggressive or deranged. They’re just people, like you and me. If you put us in certain situations, we’re more likely to be racist or sexist, or we may lie, or we may cheat.” While the study results have been repeated, considerable debate about what conclusions to draw remains.

Somehow, in this controlled environment, we shutoff our values and performed the unthinkable. Clearly, there is something more to the fabric of humanity than simple values. Empathy plays a role in this. But we first need a way to classify and apply empathy. We need a taxonomy of empathy.

A Taxonomy of Empathy

Actor Alan Alda has devoted the latter half of his life to understanding empathy and scientific communication. His new book released last month, “If I Understood You, Would I Still Have This Look on My Face?: My Adventures in the Art and Science of Relating and Communicating” is an excellent treatise on empathy and I highly recommend it. Alda is the namesake behind the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science. Alda uses an evolutionary empathy model with the following levels: mirroring, emotional, and conscious empathy (leading to what he called “dark” empathy and “theory of mind”). As you can see from the Pezeshki empathy pyramid below, that’s not too far off from the model applied in this book.

Mirroring: Alda has created a series of exercises to develop empathy in scientific researchers. One of the first activities for participants in his summer course at the Institute is to develop mirroring empathy. Before they know anyone, Alda puts pairs on stage and asks them to mimic each other’s movements precisely without talking or leading. That’s an incredible challenge that requires listening and observing every bit of information from their partner as possible. You have to get into their head and almost know what your partner is thinking. Reliably though, with practice people get it — and before they know it they even start completing each other’s sentences. Soon enough, participants know how they need to say things for their partner to understand them.

This technique works so well because mirroring neurons are both foundational and common in our brains. Even before we could speak as a species we knew how to mirror the behavior of others, and it’s something that can be observed throughout the animal kingdom, or any schoolyard playground. In many ways, our entire early-life development is centered around development of mirroring behavior — from waving hi and smiling at age 1 to following instructions for a mathematics calculation at age 17. With just our eyes we can say to others, “I’m listening and I know what you’re thinking.”

The lack of mirroring empathy is also apparent. Those diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders often show a lack of mirroring emotional states early in life. It’s not that those with autism are unable to mirror, we’re just working out what types of mirroring are inhibited.

Emotional: From his acting career, Alda knows how to show an emotion when prompted. He’s found though that others have a very hard time showing and identifying emotions from a simple facial expression. If you’ve played Pictionary or Emoticon in Cranium, you know too how hard this can be. To investigate the effect of emotional identification on empathy, Alda initiated and was a participant in a study to identify and count emotions over a several day trial. The result: the more time you identify emotions in others the more empathic you become (as gauged by a standard empathy quiz). Imagine the difficulty of trying to read emotions without facial or verbal feedback!

Emotional empathy can be disrupted by stone-walling and taunting. Teaching someone not to respond, or even acknowledge, certain emotions, or that certain emotions are wrong.

Rational: Teaching someone how to think and respond in a potential situation when nobody is around to assist them is not easy. It requires a capacity for rational thought! But how do we imbue others with this programming when it isn’t always possible to recreate the situation? Stories like the one at the start of this chapter are key. Researchers have found that when you tell a story to someone who is into it, the same regions of the brain light up in both the story teller and listener. Stories are the key to unlocking the brain and inserting programs to follow when it’s rational to. When I say they are the key I mean it. In today’s world we are constantly solicited for attention, people only invest time reading or listening to something if it is relevant, and they will keep reading as long as relevance and credibility or rationality remains. How to find the keyhole immediately? Start in an unexpected, but rational, way.

Rational empathy disruptors come primarily comes in the form of Sociopathy. Sociopaths deliberately disrupt the social networks of others, minimizes the connections necessary for rational empathy to build within a social network. Authoritarians are common sociopaths as isolating individuals by disrupting their connections to others allows for the authoritarian to consolidate and maintain their power and control.

Conscious: Alda ended his empathy taxonomy at the rational level, however proceeded with a section on “dark empathy”. Dark empathy, as described by Alda, is using empathy against someone. Psychopaths use “dark” empathy to trap their prey. Gaslighting, or construing facts and events to deliberately cause someone to question their sanity, is a common way this empathy disruption manifests. This is directly analogous to conscious empathy in the Pezeshki taxonomy shown in Figure 1. Empathy isn’t all gum drops and lollipops. Knowing empathy and the empathy of others can be used for both good and evil. In the great book “Never Split the Difference: Negotiating Like Your Life Depends on It” author Chris Voss shows how the FBI international hostage negotiation team uses conscious empathy (called tactical empathy in the book) to help resolve hostage crises. It turns out empathy is key to a happy ending. But it’s also easy to see how difficult, and valuable, it is to function at this level of empathy. Just like the energy/value levels described earlier, these levels are nested and evolutionary. To get to higher levels requires a minimum ability at the lower levels. Just think about the number of ways and experiences you need just to generally relate to others!

Global: is exactly that. Knowing the empathy of everyone in the broader/global v-Meme system. The internet will eventually enable this, hopefully sooner than later. It’s already out there in some engineers at Facebook and Twitter watching the global changes in real time. It’s analogous to the Second Foundationers in the Foundations Trilogy or the Children in Childhood’s End. Sorry to leave it at fictional references — it’s an open-ended evolutionary model. Who knows what will come next?

As you can see, there are a number of nested ways to understand empathy, on many levels in society. In any given situation I have a number of ways I could respond and am always considering how best to respond. Turns out that this is closely coupled to the laws of thermodynamics.

The ways of understanding entropy

The same pattern of increasing complexity can be applied to empathy/entropy as we applied to values/energies in the last chapter. The entropy of a molecule system is directly related to the number of ways/states it can access with higher modes built and enabled by the lower modes. Empathy/entropy too is a fundamental property in thermodynamics and cannot be directly measured. But how can we simply explain and understand entropy? Let’s look at the history.

Entropy was first defined as a thermodynamic property by Rudolf Clausius in the early 1800’s after extensive application of the Saudi Carnot’s principles of efficiency limits for steam engines. Clausius equated entropy with waste, or disorder, the opportunity for useful work lost forever to the heating of the universe. Most scientists and engineers still view entropy in this dismal way.

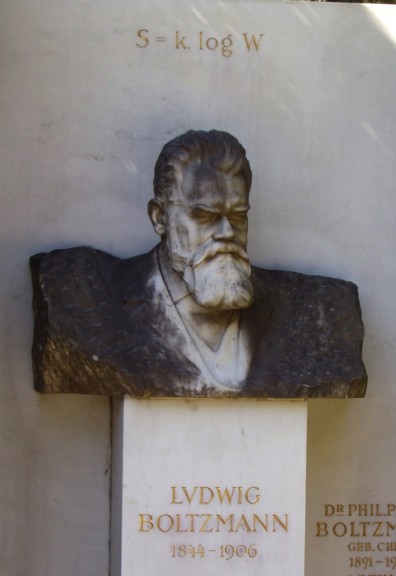

Ludwig Boltzmann discovered the nature of entropy in the late 1800’s. Boltzmann was a physicist from Vienna. His first major contribution to science was derivation of the ideal gas law Pv = RT from purely statistical based arguments – no measurements involved, just free atoms modeled as billiard balls in a container with a statistical distribution of characteristics.

Boltzmann saw the world through a statistical lens of probabilities. His next discovery was even more paradigm changing. Boltzmann realized that the statistical distribution of the molecular properties was important. A thought experiment similar to the one shown in the figure below was helpful with this. Which molecular ratchet do you think is more capable of extracting work from the atoms in the system? If you thought the one on the left, you are probably correct. Which system do you think is more ordered with lower entropy? Again the one on the left is probably the right answer. Richard Feynman has used this atom-scale ratchet-wheel analogy to describe how you can’t build small devices to harness “free energy” currents around us — the more entropy the molecules have, the less the wheel could work.

Molecular ratchet for work extraction with atom distributions.

This line of thinking led Boltzmann to realize that the microscopic entropy of a system is related to the statistical distribution of particle energies. The higher the number of ways an atom, molecule, or particle can occupy a space (different velocities, speeds, vibrations, rotations, etc.), the higher the entropy of the system. This eventually led him to derive a mathematical expression for the entropy of a statistical system:

S = k log(#ways)

In general, his conclusion for a theoretical or statistical system was that the entropy of the system is a constant multiplied by the logarithm of the probability, or number of ways, that something can occur. The life of Boltzmann is a fascinating story in itself and worth a read. He believed in his equation so much that he even had it engraved on his tombstone.

Boltzmann’s tombstone with his famous equation.

Although heat and temperature were used to derive entropy from a classical perspective, starting from a statistical point of view allows entropy to be applied to many more things than classical heat and thermodynamics. Boltzmann’s equation continues to come up in many unexpected places. Claude Shannon found the same equation when studying the transfer of information during communication. Information entropy is behind the game everyone plays as a kid where you whisper a defined sentence into your neighbor’s ear, your neighbor whispers it into their neighbor’s ear, and so on down the line. Usually the end result is quite different or disordered from the beginning. The amount of disorder is directly related to the number of ways or times that it was communicated during the transmission.

Let’s try another example: the game of Hangman. I’m thinking of a five letter word that starts with the letter “z” z _ _ _ _.

Any guesses? How about now: z _ b _ _?

If you guessed “z e b r a” you got it.

Let‟s try another five letter word: _ e _ r _.

Having trouble?

This one is also “z e b r a“. So why is the first example easier to solve than the second example? The answer lies in the number of ways, or the entropy of the letters “z‟ and “b‟. These letters are used in only a few ways in the English language, they have very low entropy and a smaller chance of a chaotic or disordered number of words they can be used in. The letters “e‟ and “r‟ aRE all ovER the place. ThERE aRE a numbER of woRds that usE “e‟ and “r‟. These letters have much higher entropy and subsequently it is much more difficult to guess the word they are associated with. Information entropy is partly behind the points individual letters are worth in the game of Scrabble.

Think about that the next time you come up with a password or code.

Statistical entropy comes up in a number of other fun situations that are fascinating to think about, try some for yourself:

- Entropy of a crosswalk or intersection as a predictor of accidents. Is a roundabout more entropic than a 4 way stoplight?

- Entropy/diversity of a forest as a predictor of resilience to disease and natural disaster. Which is healthier? The old growth forest or the replanted clear cut? It’s a tough one and the answer depends on context. My logging friends will give a very different answer than someone from the Sierra Club.

- Entropy/memetic diversity of a society as a predictor of resilience/robustness. Your trivia team’s success likely correlates with the diversity of the team.

Just like learning, entropy is a one way street. Entropy gives time a direction. Go ahead. Pull up videos played in reverse online. You’ll laugh. Why? You know that’s not the way it works, and to make it ok, you laugh about it. We know that’s not the way it works because we can see entropy — and we know in the video that time isn’t going the right way. Once you’ve learned entropy — it’s irreversible. Go ahead and try to get this out of your head after you’ve applied it. There are many ways to understand entropy beyond pure ‘disorder’.

Now think about empathy as a form of social entropy. A simple mirroring smile says something, but not a lot about how someone views you or someone else. Mirroring is the ‘e’ or ‘r’ of empathy. Watch someone try to psychopathically manipulate or gaslight someone and you know a LOT more about how they view the other person. Conscious is the ‘z’ or ‘b’ of empathy.

When I started thinking about empathy and society, my friend Dr. Chuck tried to use mathematical expression to describe how empathy changes. He described mirroring as an on or off behavior. I knew this was similar to quantum spin flips which are entangled. He described emotional as a linear response based on the time of emotional connection. I knew this was analogous to the entropy of translational energy modes in atoms or molecules. He described rational as a coupled differential equation with multiple solutions/modes. I knew this was analogous to the entropy of ro-vibrational energy modes in molecules. He knew conscious/global empathy worked through multiple players at a distance. I knew this was analogous to electronic/plasma states of molecules. What’s more, Dr. Chuck’s empathy levels were nested just like the entropy/energy modes of molecules. Empathy could readily be modeled as social entropy, and may’be it even is social entropy.

To try to prove this, Dr. Chuck gave me one of his key riddles to solve: Why are groups of people always able to produce more incredible designs and ideas than any of the individuals acting alone?

The Empathy of Mixing

The entropy of mixing is defined in thermodynamics as the increase in total entropy observed when initially separate fluids in equilibrium mix without chemical reaction. The entropy goes up because a considerable amount of work would be required to separate the fluids again, work that you can only return a small fraction of. The entropy of mixing always leads to an entropy higher for the mixture than the pure components alone, and the maximum entropy of mixing likely occurs near an equal parts mixture:

This entropy of mixing is provable directly from statistical mechanics and immediately analogous to information entropy.

From a culture standpoint, consider the wedding ritual of mixing two different colored sands together — it’s a symbolically irreversible union. The same likely applies to the mixing of cultural v-Meme stacks. Dr. Chuck has always said that one of the key things holding me back in life is my experience of other cultures and he’s right. It’s very difficult for me to empathize on a global level with so little experience.

So here’s a key rule of the chemistry of empathy — the empathy of mixing cultures is higher than any of the cultures alone. One of Dr. Chuck’s grand challenges, the riddle of how we’re able to be smarter and more empathetic together than any of us alone, is solved by this analogy from thermodynamics. Because we’re more empathetic and entropic together, in other words the more accessible ways we have to connect and solve problems.

Thankfully, even simple binary fluid mixtures have much more complexity. Just because they mix, the same as cultures, doesn’t mean they mix evenly or stay mixed under all conditions. Enter miscibility.

In thermodynamics, two fluids are considered miscible when mixed and form a homogenous solution in all proportions. Basically a random mixture with no precipitates, which is what ideal fluid mixtures always form. Whether fluids are miscible or not depends on the enthalpy of mixing, also known as the heat of mixing. Enthalpy (H) is equal to U + Pv. Hence if the differences in perceived societal values (U) or stress and density are too significant, and the available resources (T) drop below a critical threshold (known as the critical solution temperature), the fluids or cultures will unmix and form precipitates.

This concept of miscibility is readily observable at many levels in society. From marriages where the perceived values become too different and resources strained, or in large scale cultural mixing like we are observing with the immigrants fleeing from wars to Europe. It takes considerable resources (T) and empathy (S) to overcome the cultural drivers towards in-group/out-group formation of precipitates. But when successful, cultures will be more empathetic and better for working towards miscibility. Seperation camps are seldom a good idea.

Separation happens. Sometimes spontaneously due to inadequate resources driving precipitation or too many resources causing boiling of one component and not the others. When forced it’s a highly inefficient process analogous to genocide — we strive towards higher empathy, it makes us better than any of our constituents alone. Sometimes, though two fluids are so unbalanced chemically (alcohol and water are a match for the ages) that they need each other and when in the right proportions, no degree of resources (T) or perceived need to change (U) can separate them. They’re stuck together. These are known as azeotropes. A social example could be those that have empathy receptor deficiencies (Asperger’s) with those that have empathy processing deficiencies (psychopathy).

One thought that came to me when writing this post, I teach that whenever you have a gradient, whether chemical or cultural, there exists a potential to do useful work. The chemistry of culture mixing presents considerable economic potential in the form of new products, concepts, and services. Instead of walling out cultures, there may be opportunities for revenue generation in these culture gradients in the form of schools and design firms.

The Empathic Civilization

In his 2010 novel “The Empathic Civilization: The race to Global Consciousness in a World in Crisis” Jeremy Rifkin writes an incredible historical recounting of humanity’s increasing empathy. Rifkin writes, “At the very core of the human story is a paradoxical relationship between empathy and entropy… The irony is that our growing empathic awareness has been made possible by an ever-greater consumption of the Earth’s energy and other resources, resulting in a dramatic deterioration of the health of the planet… Can we reach biosphere consciousness and global empathy in time to avert planetary collapse?” Quite a paradox indeed.

I’m not going to resolve Rifkin’s paradox for you. I’m going one step further to say empathy is the social manifestation of entropy. What is clear is the rapid pace with which social media is improving in the empathy department. It will eventually connect society at the global level in orders of magnitude stronger and more empathic ways than ever before. I consider the increase in empathy to be the 2nd Law of Humanity. For humanity to continue or increase, so must empathy.

Look at the history of life on our planet. Empathy could be the only trait of life that has consistently increased regardless of epic or die-off. Yes we’ve had our stumbles and gaffes. When we recover, we generally find new and better ways. As you’ll see, the chapters of this book cover this sophistication versus evolution phase change from many ways.

Back to Social Media and the Milgram Experiment

It’s fairly common these days to find an elder politician who feels humanity has gone astray and civilization is doomed. Just look at the verbal abuse, attacks, and how easy it is to end up in a fight on social media. Looking at the above empathy layers, how many would you say are fully in use when on Twitter or Facebook? About the most we get is a thumbs up “I hear you.” That’s it. A picture is worth a 1000 words (990 of which may be irrelevant), but at least you can read the facial ques to try to connect emotion. Sometimes we get a story without the facial ques and audible emotion. Social media, in it’s current form, robs us of nearly all the empathy cues we’ve evolved to help humanity. The trapping of social media is ease. We’re now able to stay informed, and somewhat empathic to our family and friends with a frequency over a space not possible just decades ago. As a result, many of us are spending significant portions of our lives in this low-empathy environment. With a foundation of mirroring neurons, it’s no wonder we’re so quick to fight!

Bring this back to Milgram’s experiment we started this chapter with. Put yourself in the student’s shoes. You’re likely a college student who’s told what to do by an authority professor all day long and simply trying to mimic their techniques. You volunteered in this weird science study just to make some beer money. Just do what they tell you and get out so you can have fun. After being led down the bare, dimly lit halls, you’re put in the room and given the instructions and that’s it. You can either press the button or not. Talk about a low empathy environment.

I wonder if anyone has thought to redo Milgram’s experiment but try Alda’s exercises above between the “teacher” and “student” beforehand. We may get a couple of play tickle shocks for fun, but likely no more. Empathy and our connections are what will save us.

Here’s hope for the future!

(Note: this post is one chapter of what could become a book someday. The other chapters can be found here: https://hydrogen.wsu.edu/dr-jacob-leachman/ )