[Note: This post was adapted in January 2020 to reflect WSU’s hiring of Nick Rolovich.]

It didn’t make sense but I ran my assignment anyways. But I was just a lineman in high-school. I picked up the linebacker I was assigned to, only to watch another make the play. I was frustrated. So in the middle of practice, I stopped the whole team and did the mutinous act of questioning the coach. “Coach, can you help me understand this because I’m missing something.” I went through all of the assignments of the players on that side of the field. “Why am I not picking up the other backer, is it because of another defense that the other team is likely to run?”

Coach Menegas was widely considered an offensive genius in the state of Idaho. He ran a spread offense passing attack scheme heavily influenced by Dennis Erickson and Mike Price. Menegas laughed and said, “The lineman understand the offense better than some of the coaches!”

The very next play I tripped over one of the white lines on the field…

Anyways, many of you know that collegiate football was a big part of my past. This influence is documented in my TEDx talk among other places. In college I was recruited to play offensive tackle by Tom Cable– who was the assistant head coach and line coach of the Seattle Seahawks (he had a hand in Marshawn Lynch’s success). My position coach in college was Tim Drevno, the former 49ers line coach from 2011-2013 (who sent 3 lineman to the Pro Bowl during that span) and was the University of Michigan Offensive Coordinator. I backed up Jake Scott (also at Idaho and from my high school), who guarded Chris Johnson when he set the NFL rushing record with the Titans, and Peyton Manning when he won a Super Bowl ring. Suffice it to say, I know pro-style, a.k.a. West Coast, offense schemes.

So let’s compare and contrast the Pro-Style and spread systems.

Basics of the Pro-Style and Spread Systems

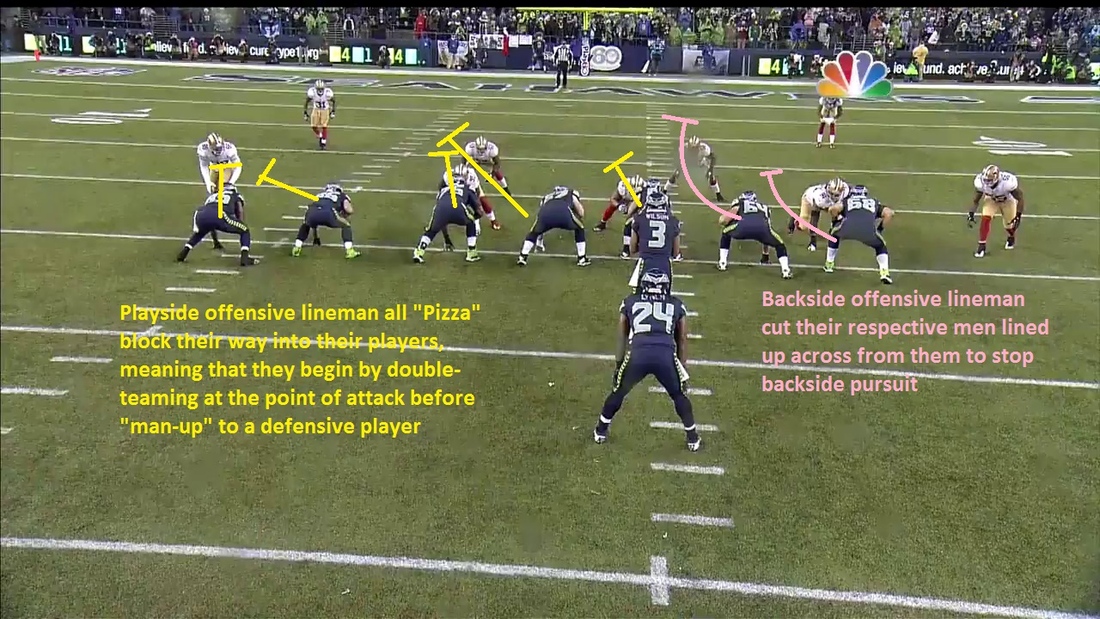

“Pro-style” offenses, commonly fielded by Stanford and Washington, are often referred to as the “West-coast” system originated by Bill Walsh with the San Francisco 49ers during the 1980’s. The entire offense is based around the zone run/block scheme, shown below.

The zone-blocking scheme begins with each offensive lineman running at a pre-defined angle relative to the line of scrimmage and either blocking people directly in their zone along that line or shedding the defender into a neighboring zone (a.k.a. lane or silo). Defensive stunts don’t matter as there is a lineman for every zone. This in-turn requires teams to stack the box to stop the run, opening up the play-action pass with the quarterback rolling out of a typical zone-run block to stretch the defense away from where the run would have gone. The lineman in this scheme are huge and slow — it doesn’t matter — come rain, snow, or a princess running the ball, all that matters is at least 3.3 yards every down. If you do, you ground-and-pound your way to a first down while chewing up the clock and controlling the game. It’s methodical and reliable.

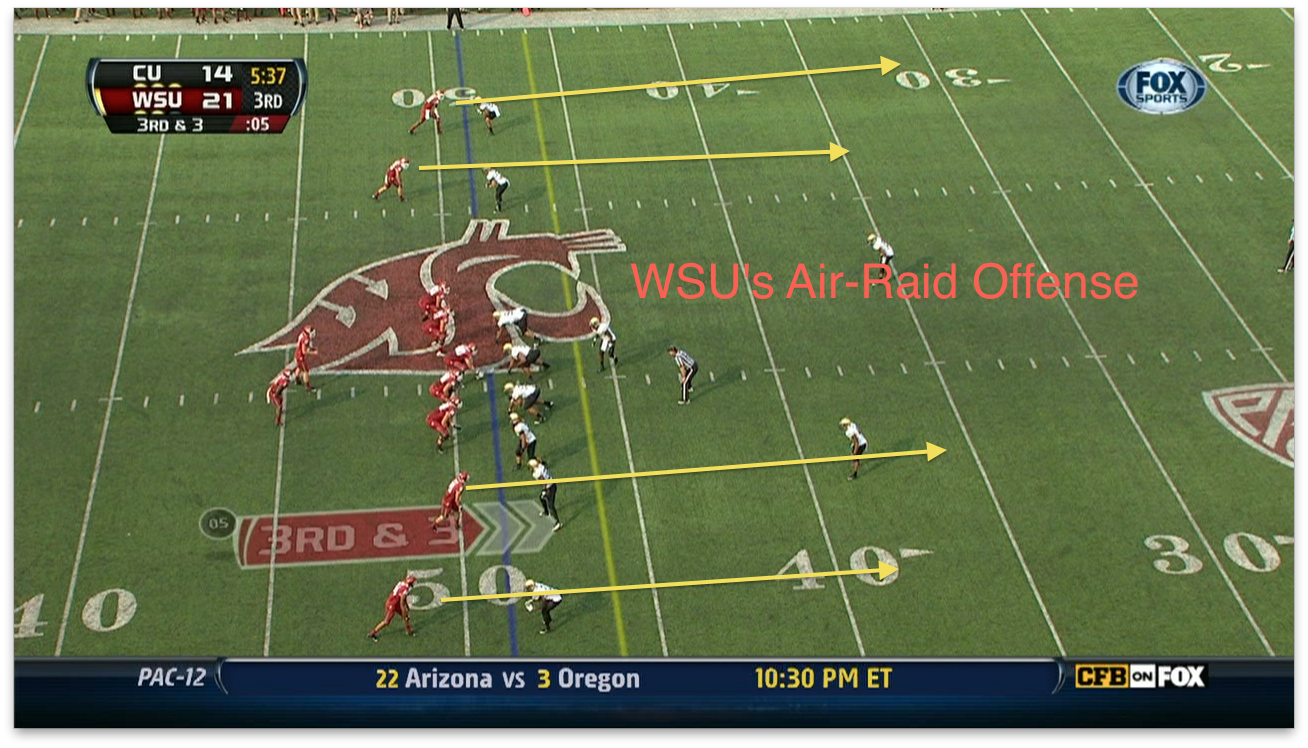

For pretty much my entire life WSU has implemented a version of a ‘spread’ offense. We’ll get into why in a minute. The image below shows a classic “Air-Raid” offense originated by Iowa-Weslayen and WSU former coach Mike Leach at Texas Tech in the 1990’s:

The foundation of this system is a shotgun spread-formation passing attack intended to create at least one open player every down. Here’s an article that discusses the origins at Iowa-Weslayen. Somewhere there will be a mismatched defender on a receiver, if only for a moment, that will allow for a perfectly timed ball to be caught. The quarterback will find the mismatch, exploit it, else the defense is spread far enough down the field for a 10 yard QB keeper. Luke Falk once mentioned in an interview that Coach Leach tell’s him to throw it unless he thinks he can run for 10 yards.

The keys to the Air Raid are simplicity, space, and speed. Leach was able to connect more areas of the field, from a much simpler offensive scheme. It’s directly analogous to Miles Davis using atonality to more simply connect scales in the epic Jazz album “Kind of Blue.” You can reliably predict when things will change based off whether they connect more things, more simply.

Before we bring this back to the “Run and Gun” — and how it’s a better evolution of the spread than the Air Raid — let’s talk systems theory for a minute.

Using Design Theory to Compare ‘Pro-style’ and Spread systems

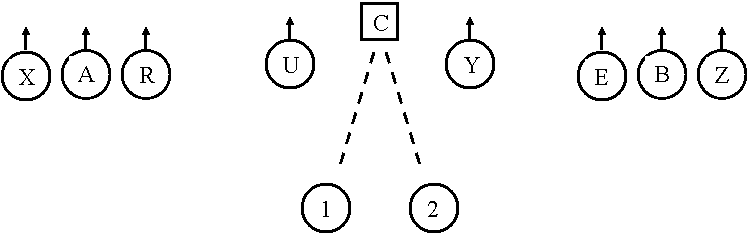

Now let’s relate these two schemes to the information flow diagrams of spiral value memes. Remember that these are generic information flows that are very difficult to represent in 2-D but I’m guessing these are close enough for most to associate to football. There are multiple books on these system diagrams, rather than wade into the nuances I’ll let you simply associate for yourself.

I associate the old school option play with diagram C and the West-coast offense with diagrams C & D (a.k.a the authoritarian and legalistic memes). The legal meme epitomizes the steady progress, predictable process, and reliability of the west-coast system. Once it’s working, turn the crank, little thought required.

I associate spread systems with diagram E or the performance meme. The performance meme is based on exploiting person to person match-ups with the opportunity to spread the ball around the field based on real-time reads. It’s higher entropy, requires more empathy for the defender and receiver, higher scoring on average, and harder to defense. Yet the scheme connects more regions of the field in a simpler, more powerful way than other schemes — that’s how the thermodynamic property that I know and teach, called entropy, works.

So how are the Run and Gun and Air-Raid different?

The Air-Raid’s first priority is to create space in the field, then quickly attack the space. This is why the vast majority of throws are short pass/slant routes. Although quarterbacks have autonomy to adapt to the defensive set, if the defense clouds the space by being able to get pressure with only three down defensive linemen, then all of the throwing windows compress until everything becomes a scrum and challenging to predict (see Apple Cup 2013-2019, and any other game where a team had more time to prepare a defense). This is where Leach’s stubborn ego about the simplicity of his system repeatedly doomed WSU as there simply was no plan B. This is the only way it’s possible to explain having a top 10 first round pick in Andre Dillard and not being able to run off-tackle. My high school offense led the state in rushing from a spread based scheme, it can and should be done with an athletic tackle. I’d talk to some of the offensive lineman in passing in airports and on campus, after a short talk, they’d all lament that they were not being coached well (I was taught not to make some of their mistakes in high school). I think I was literally going to be sick if I watched another Apple Cup where the o-lineman were standing around powerless, watching the quarterback hoping for a play to be made. Any scheme that doesn’t utilize all of the players on the field, every play, is leaving talent under-utilized.

The Run and Gun starts very similar to the Air-Raid by spreading everyone out with a simple scheme to force assignments and sets. But rather than stopping at a quick decision, the Run and Gun has another level. Rather than create space for a quick attack, the Run and Gun’s more balanced, layered attack creates both time and space, forcing a safety to make a decision on which space they have time to defend: the deep vertical or the deep out. In turn the receiver and quarterback read this decision and adapt accordingly. In other words, the Run and Gun is more adaptive and empathetic than the Air-Raid, which goes hand-in-hand with performance. From a player standpoint the Run and Gun is minimally more complicated than the Air-Raid, it’s a simple heuristic process to work through from just about every play set. All you have to do is line up in formation, remember the 1st route, and then the second layer. The additional time requires more of the offensive lineman to field blitzes and guard the quarterback while the layers unfold. This stretching of the field also allows plenty of room underneath for running, which Nick Rolovich seems more happy to do.

So what does this mean about future offenses?

Physical limitations necessitate an upper limit on physical strength, speed, and endurance of the game. We’ve flirted with these physical limits for over a decade now and it’s tough for a smaller school like WSU to compete with the big people arms race of the West Coast system. In short, the real opportunities in football currently are real-time adaptation through autonomy enabled by increased communication, and sustainability by promoting increased load-leveling to different areas of the field, while decreasing repetitive impact to key players.

Enter diagram F above and the communitarian meme. This meme is typically associated with low-carbon lifestyles, co-ops, and anything but football. But I’m here to tell you it’s where things are headed. The clustering of players, tight communication networks, and sustainable values are key indicators. But what will this look like on the football field? A great example is the A-11 offense that emerged in high-school football in 2009:

Notice the clustering of groups that intentionally increases entropy (# of ways a play can unfold) and aids communication. What this also allows is increased protection in the form of blockers to protect the ball carrier in different areas of the field. This future allows more screen plays, more athletic and involved linemen, and real-time adaptation within the clusters.

The next meme-level, level G, is represented poorly within the diagram above. At this level we become aware of the unique roles and necessity of all of the fundamentally different offensive schemes. The New England Patriots, and Kansas City Chiefs are two examples of the few teams I’ve seen that can shift quickly between west-coast and spread offensive schemes. The reason they likely don’t go to the communitarian meme (diagram F) often is unnecessary rules governing the minimum number of down lineman next to the center in formations.

One of the keys to note, just because you have an excellent structural philosophy for your offensive system, doesn’t mean you have the empathy/culture/chemistry between players, on and off the field, to fully perform with the system.

If we don’t legalistically create rules to preserve the status quo of the game of football, we allow for innovations that can actually improve the safety and sustainability of the game.

Regardless, I’m really excited to see Nick Rolovich’s Run and Gun system back on the Palouse.

(Note: this post is one chapter of what could become a book someday. The other chapters can be found here: https://hydrogen.wsu.edu/dr-jacob-leachman/ )